Inside the failed plan for Monarto, the futuristic city that never was

In the optimistic 1970s, when humanity reached for the moon, South Australia’s Premier Don Dunstan reached for the stars, envisioning a futuristic metropolis called Monarto.

This wasn’t a sci-fi fantasy; it was a grand vision that promised utopia, complete with monorails, an artificial lake, and a central ‘Honky Tonk’ for its 200,000 citizens.

But this city, designed for a better tomorrow, never saw the light of day.

Why did Australia’s most ambitious urban dream become its most spectacular ghost town, and what lessons does it hold for today’s developers?

Dunstan’s daring dream: A utopia rises from the mallee

It was a time of boundless optimism, where the impossible seemed within reach.

If we could put a human on the moon, surely we could build a perfect city from scratch. Premier Don Dunstan certainly thought so.

In November 1972, he proudly unveiled plans for a satellite city, initially named Murray, then Monarto, to rise from the Mallee plains, about 60km from Adelaide and bordering Murray Bridge.

MORE NEWS

‘Costly, but worth it’: Aus’s forgotten flying billboard

The luxury reef resort Australia forgot about

$100bn ghost city’s shocking reality exposed

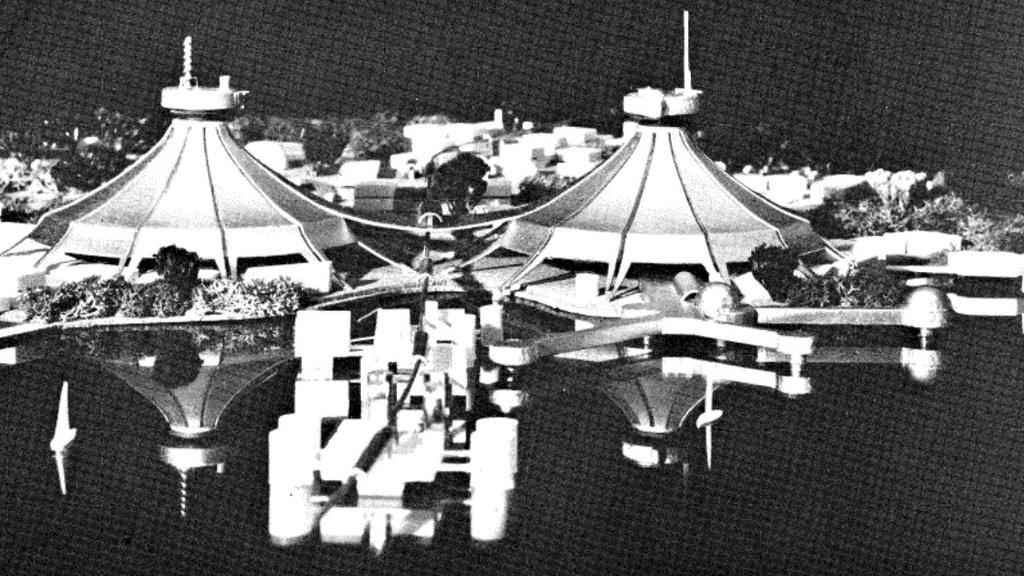

This computer-generated concept image shows Monarto’s CBD, with futuristic buildings reflected in a man-made lake. Image: Studio Kazanski/Shankland Cox.

Even an emblem for the city of Monarto had been approved.

Dunstan described it as “unlike any other city in Australia,” promising “a new, refreshed and natural place in the sun… a shady, walkable, easy-to-live-in city.”

The vision was breathtaking: a city designed for 200,000 residents, the first major new Australian centre since Canberra.

Citizens would glide on monorails, and the social heart would be a futuristic Honky Tonk with tent-like roofs made of “the latest lightweight high-tech materials,” nestled beside a sparkling artificial lake.

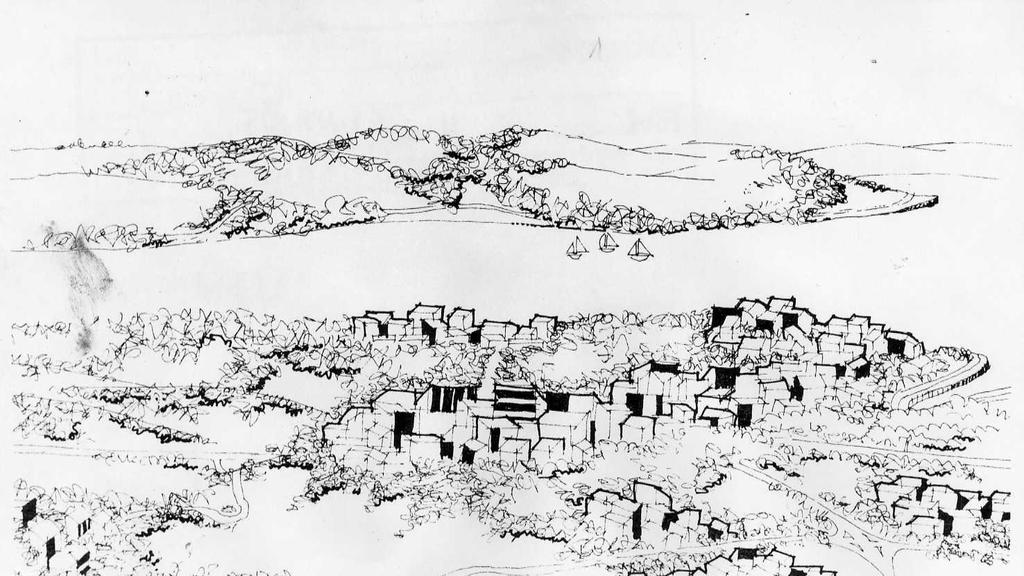

The Mediterranean style of Monarto is featured in this 1975 artist’s impression of the city centre with the lake in the background. The impressions show no plans for multistorey buildings but the centre would have feature many parks and plazas.

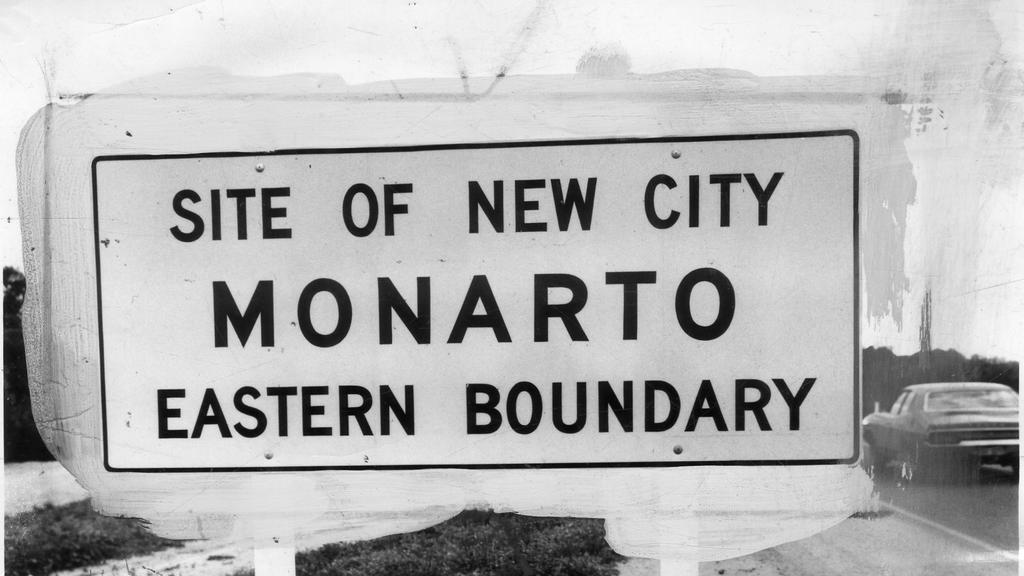

Sign marking the eastern boundary for the planned future city of Monarto, South Australia.

The state government moved swiftly, according to media reports, acquiring a vast 16,000 hectares.

In a single day, a quiet farming community was changed forever, all in the name of progress and a bold new future.

Monarto: The blueprint for a better life

Dunstan’s motivation was clear: Adelaide’s population was booming, growing at 3.3 per cent per year and forecast to hit 1.3 million by 1991.

He feared the capital would become smoggy and congested, sprawling uncontrollably.

Monarto was to be the “escape valve,” a planned counterpoint to urban sprawl, particularly to protect Adelaide’s valuable wine and almond-growing regions.

The Department of Urban and Rural Planning, alongside Dunstan, began to imagine a city where the latest theories of urban and social planning could be put into practice.

Journalist Rex Jory recalled suggesting a lake, prompting Dunstan’s enthusiastic vision of sailing ships and restaurants.

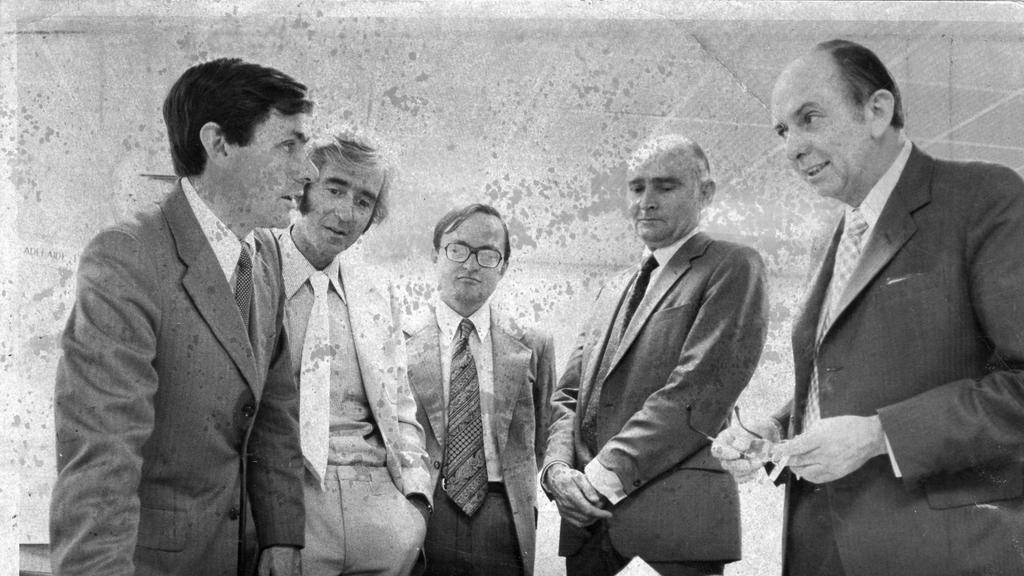

SA politician Don Hopgood (l) with (l-r) Newell Platten, John Mant, Tony Richardson and Ray Taylor, members of the Monarto Development Commission meet at Greenhill Road, Unley to discuss plans for the future city of Monarto, South Australia.

SA former politician Premier Donald Allan Dunstan (2nd l) examining the site for the new city of Monarto May 1982. don

This idealistic zeal permeated Dunstan’s speeches.

“Monarto will have a distinctive and lively city centre, homes to appeal to all income groups, abundant open-air recreational and park space and literally millions of trees,” he said when a concept plan was revealed in 1974.

“It won’t be a one-class or one-industry city.

“It will contain a variety of manufacturing, commercial, academic, scientific and government ventures; it will have a balanced, self-contained community.”

Rocky Gully Creek would be dammed to form the central lake, with the CBD on its foreshore, complete with a theatre.

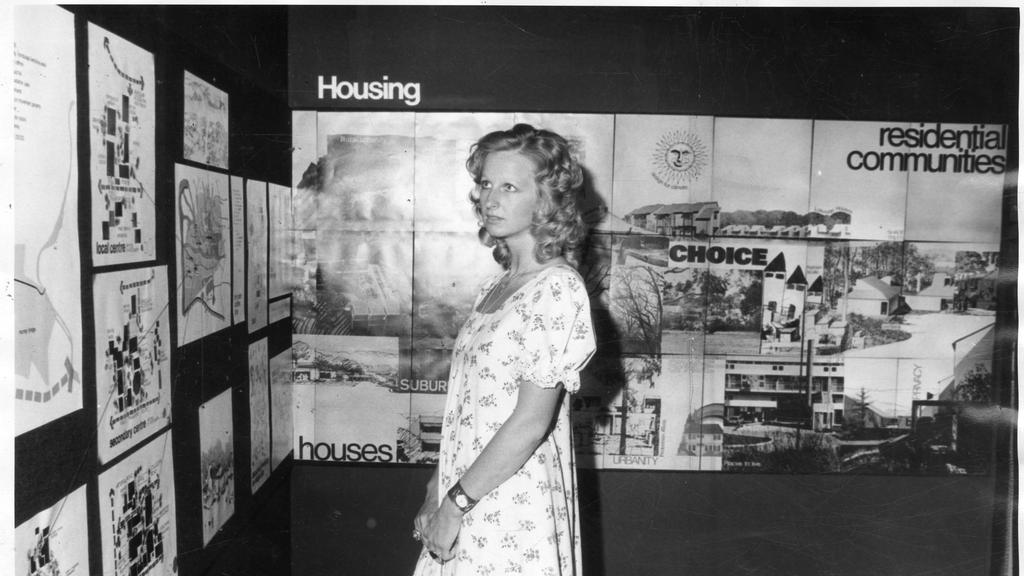

Exhibition hostess Ms. Olga Bondarenko inspecting ideas and plans for the planned new city of Monarto, South Australia.

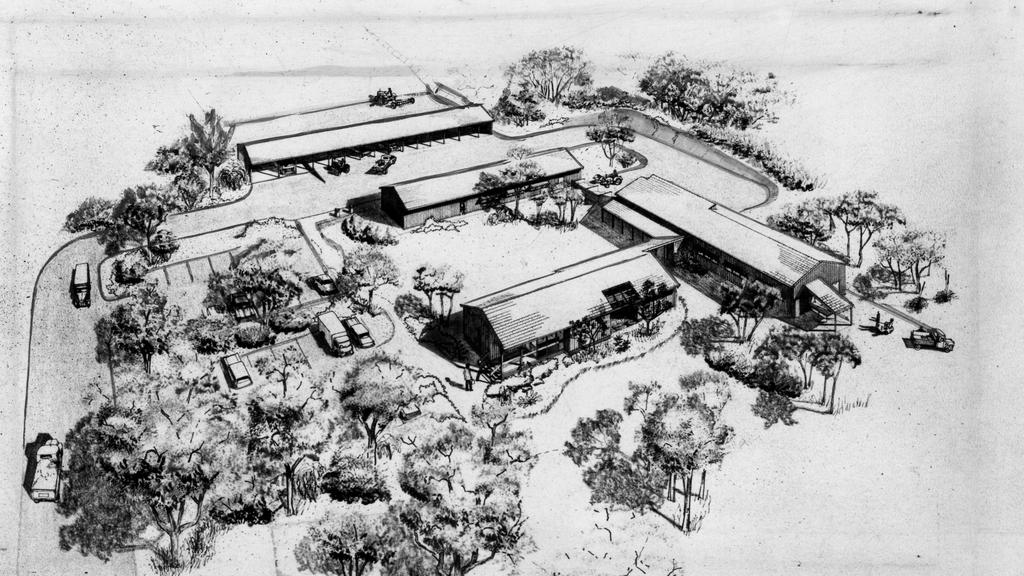

Developer’s drawing of Woods and Forests Department Tree Nursery complex planned for the future city of Monarto, South Australia.

Green corridors would crisscross the city, allowing residents to ride horses through it, always a short walk from a park, school, shop, or public transport.

“In terms of social facilities, recreational facilities, ease of getting to and from work and actual living conditions, the residents of Monarto will be the most pampered urban dwellers in Australia,” Dunstan said.

The federal government, under Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, backed the dream with $10 million in funding – approximately $66 million in today’s dollars – as part of a national push for new cities.

The dream unravels: Why Monarto never rose

Early reactions to Monarto were largely positive, though two key concerns emerged: was it too close to Adelaide to avoid being swallowed by its growth, and could it attract private-sector business and public-sector staff?

As it turned out, the first concern was unfounded, but the second became a fatal flaw.

Businesses were wary of the site’s distance from both Adelaide and a reliable water supply, which would have to be piped in.

Plans to relocate state government departments to Monarto to kickstart its economy were stymied by public servants reluctant to leave Adelaide for the Mallee’s “dry expanses.”

However, the most significant blow came in 1975 with the release of the Borrie Report on Australian population growth.

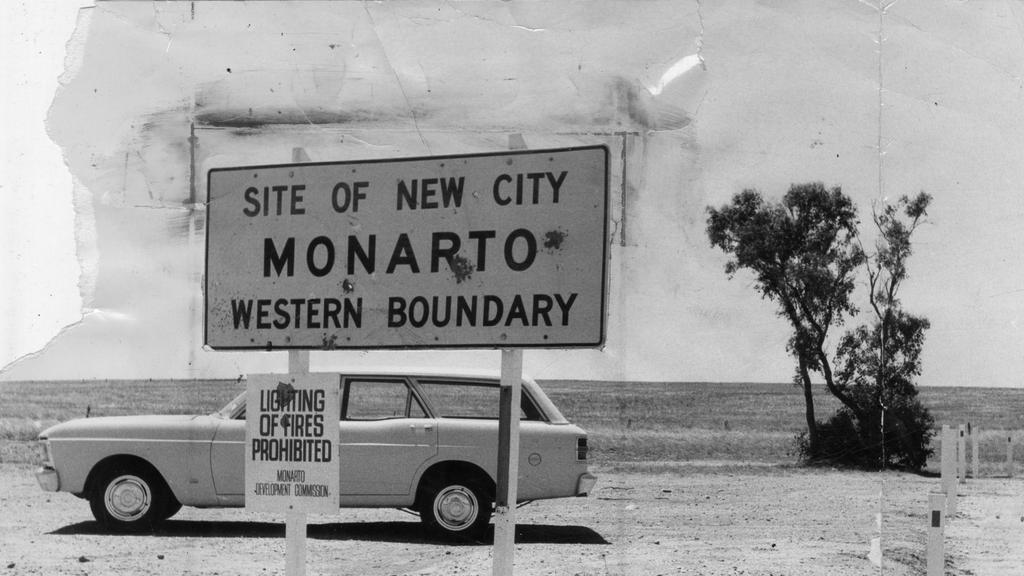

Sign marking the western boundary for the planned future city of Monarto, South Australia.

Recreation centre and oval at the site of the formerly planned future city of Monarto, South Australia, has been handed to Murray Bridge.

This report drastically revised South Australia’s population forecasts downwards.

The projected 1.3 million mark was now not expected until the 21st century, with a more likely figure hovering around one million.

Suddenly, Monarto’s planned population of 200,000 was simply not feasible.

The grand plans – the lake, the forest, the giant tent – were put on hold.

Though Dunstan briefly revived the idea in the late 1970s, clinging to the hope of revised population forecasts, by 1982, most of the acquired land had been returned to farmers.

The site’s future was instead reimagined as the Monarto Safari Park.

Echoes of the past: Is history repeating itself?

While Dunstan’s ambitious plans were abandoned, the allure of a satellite city near Murray Bridge persists.

Today, a bold $7.5 billion plan has been unveiled by developers Grange Development and Costa Property Group for Gifford Hill, just kilometres from the original Monarto site.

Billed as South Australia’s largest residential housing project since the 1950s, it envisions 17,100 new homes for 44,000 residents, complete with a new town centre, schools, and vast green spaces.

Farmer Stan Nitschke lost his property as part of a compulsory purchase by the government for the site formerly planned city of Monarto.

Farmer Robert Thiele who saw his community “ruined” by the failed 1970s vision for a major city at Monarto, just kilometres away from the Gifford Hill development. Picture: Keryn Stevens

The Gifford Hill precinct has been earmarked for development since 2009, with a consortium including the Hurley Hotel Group and former AFL footballer Mark Ricciuto already establishing a new racecourse.

The current developers, who acquired 909 hectares, are planning a 30-40 year project and even hope Gifford Hill could one day host Adelaide’s second airport.

However, for some locals, the term “satellite city” is a “dirty phrase,” stirring memories of the Monarto debacle.

According to The Advertiser, Robert Thiele, a local resident, recalled how the Monarto plan “ruined” a “beautiful community,” with farmers “virtually evicted” and prime land abandoned. He points to the same reasons for Monarto’s failure: unexpected population growth, withdrawn federal funding, and a lack of private enterprise.

However, despite the historical baggage, Thiele expresses optimism for the new Gifford Hill plans, believing “the time was now right.”

But as South Australia once again looks to the Mallee for its urban future, the ghost of Monarto serves as a potent reminder: even the most visionary dreams can crumble under the weight of changing demographics and economic realities.

The question remains: will Gifford Hill learn from the lessons of its phantom predecessor, or is history destined to repeat itself?