Chinese property developers beat a hasty retreat from Australia

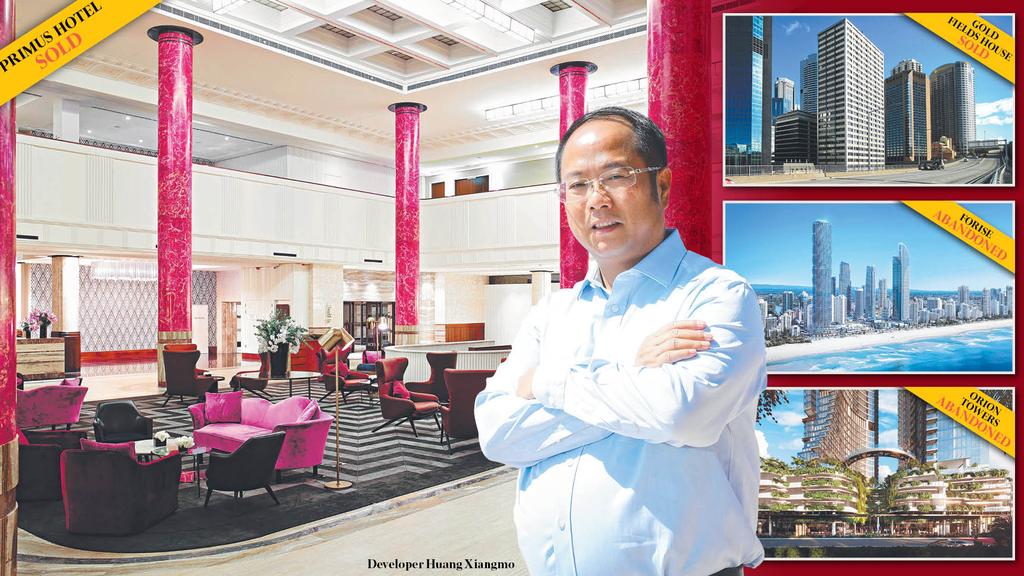

Three years ago, Chinese billionaire Huang Xiangmo was a common sight at the Sydney Cricket Ground, using his box to entertain the heavy hitters of Sydney’s real estate scene. Now the Yuhu Group chairman is barred from returning to Australia.

His property empire has been largely sold. The most recent sale from that once-sprawling portfolio was the Eastwood Shopping Centre in suburban Sydney, spun off late last month for $150m.

Huang is now down to his last few Australian properties.

It’s a similar story with almost all the major Chinese developers — from Greenland to Starryland — who aggressively expanded into Sydney, Melbourne and the Gold Coast only a few years ago.

Even Meriton, one of the country’s largest privately owned property outfits, was being sized up by Chinese interests in what could have been a $3bn deal.

Those days are long gone.

“Most of them have left,” says Meriton’s billionaire managing director Harry Triguboff. “They left because they lost money.”

Huang’s exit, which came after he was embroiled in a series of political scandals, is one of the best known examples of Chinese developers taking a much lower profile in recent years. They are still heading for the exits in areas as far-flung as the Liverpool Plains of northwest NSW, where Shenhua is offloading its rural property portfolio after reaching a deal with the state government to walk away from its $1bn Watermark coalmining project.

On the outskirts of Melbourne, a conference centre owned by an offshoot of debt-laden Chinese conglomerate HNA has fallen into the hands of receivers PwC after being hit by coronavirus and the Chinese government crackdown on mainland companies that thrusted into global real estate markets. HNA borrowed heavily to buy global assets, including stakes in Virgin Australia and hotel chain Hilton. Now it’s selling assets. Its Aitken Hill Conference Centre site is likely to hit the market shortly.

The problems don’t stop there, with even the largest Chinese players weighing up their futures.

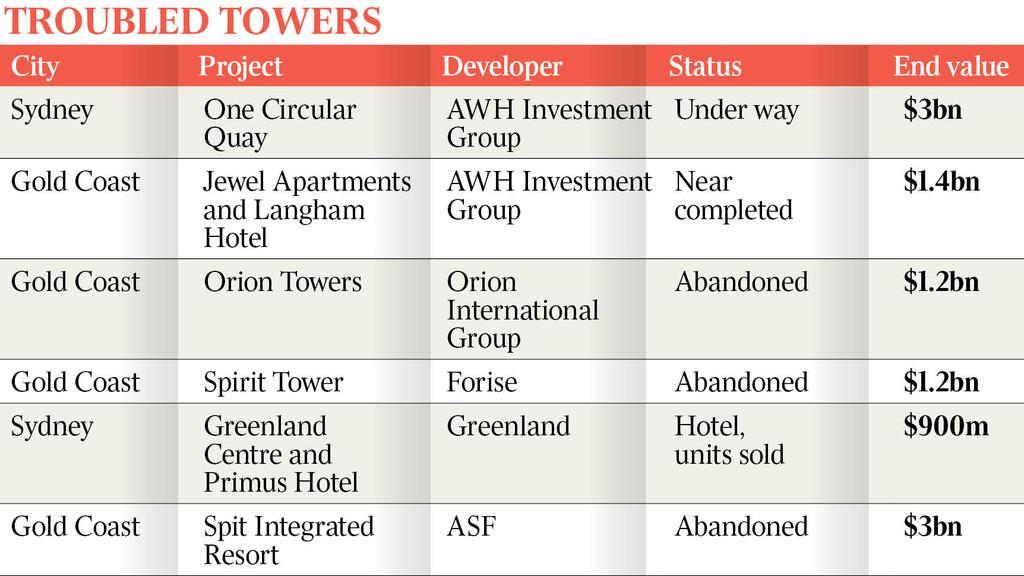

Chinese developer Greenland all but started the Chinese property boom when it forged into the Australian market in 2013, spending millions of dollars converting old public infrastructure in Sydney’s Pitt Street into the five-star Primus Hotel, which it sold this year. It has other projects on the go but experts say it has cooled on Australia. One adviser told The Australian the company was “on the way out”. Greenland did not respond to inquiries.

Most of the buildings that Chinese groups snapped up in the boom remain in their hands but the developers’ dreams of becoming a new force in Australia have been all but shattered. They faced a toxic mix of bad political relations, a tough industry, the apartment crash and China’s crackdown on capital going offshore for luxury projects. They also paid too much for apartment sites, particularly around inner Sydney.

Some major Chinese players quietly received a call to go home. Senior executives say they were told not to invest in new projects in Australia. China’s Poly Group missed out on a big Lendlease project and others quietly dropped plans to build apartments that no longer stack up, with a host of players selling out of sites in Melbourne and Sydney after realising the market was overcrowded, even before the pandemic.

Harry Triguboff. Picture: Hollie Adams

Former CBRE sales agent Mark Wizel, responsible for selling sites with an end value of more than $15bn to Chinese buyers between 2012 and 2017, says the market had cooled, partly because of politics. “I can’t remember the last transaction of significant commercial real estate in Australia to a mainland Chinese entity as purchaser,” he says.

“It’s important to understand the sequence of timing, given the hostility afforded by both Australia and China towards each other.’’

Specifically, Wizel says the Chinese government’s 2017 crackdown on investors operating outside of their home market drove the once domineering Wanda to sell its interest in Circular Quay and the Jewel Gold Coast projects.

“In more recent times, calls from government for a Covid inquiry and the ongoing tariffs on Australian goods and exports has led to a growing weakening of the relationship which might be seen to be impacting property investment from China into Australia, but the capital controls and restrictions are still in place and have not changed since late 2017.”

“Chinese investment into commercial real estate started to wane after the Chinese government implemented capital controls in 2015-16. There was a marginal uptick in Chinese investment in 2020, so it would be hard to ascertain whether the current trade stoush is having a material impact on real estate volumes,” RCA head of analytics Benjamin Martin-Henry says.

But Mr Wizel, who now runs his own agency, is optimistic Australia will be back on the radar for Chinese investors and developers.

Andrew Antonas. Picture: Sam Mooy

“I anticipate the state-owned entities will not be around for many years to come, such as those that bought the Sheraton on the Park in Sydney,” he says.

“I anticipate that within three years a return of private mainland Chinese investors and developers will be on the cards and will be needed to ensure that our development industry in particular has the capital needed to commence, deliver and complete new residential and mixed-use projects.”

Others are sticking around, as development is a slow game. There will still be big Chinese developments dotted throughout the cities and suburbs but market watchers say it is unlikely they will be so prominent again.

Those that remain have adapted to local conditions and are doing far less glamorous housing estates and office buildings, rather than glitzy hotels.

Matrix founder Andrew Antonas, who has previously sold large Chinese investors several development sites, says the developers who have remained have been quiet. Of late, however, he has seen a new confidence in them as they started cashing in from their off-the-plan apartment sales.

One developer, JQZ, is again selling luxury penthouses. It recently sold a $10.5m penthouse on the 46th and 47th floors of its St Leonards project which is under construction in Sydney.

“We have had calls from half a dozen in the last few weeks looking to buy new sites,” Antonas said. “It’s the first time in 18 months that we have been getting calls from Chinese. They have confidence in the local market.

“There’s a scarcity of development-approved apartments sites within a 20km radius of the city. Whatever sites the Chinese have overpaid for in the past, it’s all forgiven – the market has caught up now,” Antonas says. “Outside of 20km, it’s a different story. The land and housing market is the only show in town.”

Additional reporting: Joseph Lam