What happened to Sega World Sydney? Looking back on Australia’s failed theme park

Sega World Sydney may bear the unfortunate reputation as one of Australia’s shortest-lived theme parks, but its legacy as a high-tech entertainment playground that was decades ahead of its time also endures.

Operating for just under four years from 1997, the video game-based amusement park was located in Sydney’s Darling Harbour. It was the brainchild of millionaire entrepreneur Kevin Bermeister, who was inspired by similar Sega amusement parks in Japan and the UK.

In 1994, Bermeister, who ran the Australian distributor for Sega products, Sega Ozisoft, established Jacfun – the property company that would go on to build Sega World Sydney.

That same year Jacfun gained control of a 1.5-hectare block of land in the Darling Walk precinct (later to become Darling Quarter).

Bermeister approached Sega in Japan to invest in the high-tech venture. They agreed, and a joint $80 million was contributed by Jacfun and Sega to bring the ambitious theme park to life.

Former AV manager at Sega World Sydney and now music lecturer at Western Sydney University, Noel Burgess, noted the unique circumstances surrounding the Sega World leasehold.

“Darling Harbour is not actually part of Sydney City Council, but rather managed by Property NSW, which is how Kevin [Bermeister] managed to acquire such a rare 99-year lease for the block of land Sega World was built on,” Mr Burgess told realcommercial.com.au.

“Once he had secured investment from Sega and the building was finished, Kevin essentially became both the general manager of the park and landlord of the building, with Sega Japan as the anchor tenant. It was a pretty strange setup.”

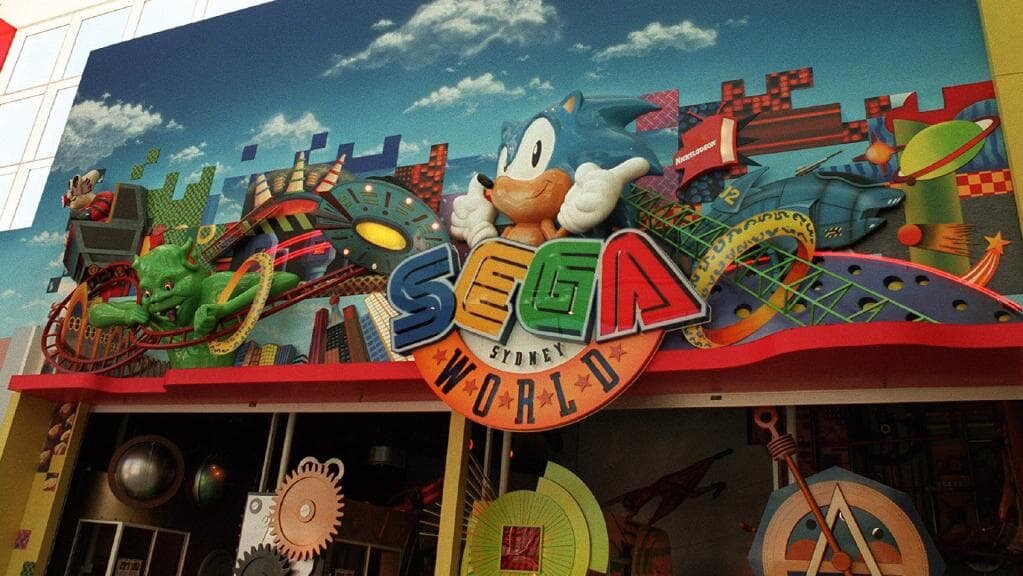

Sega World Sydney. Picture: Wikipedia

Constructed over a three-year period, the 10,000sqm park was modelled on Sega’s Joypolis indoor theme park in Yokohama, but far bigger in scale.

Unlike its Japanese and British counterparts, only one virtual reality ride featured at Sega World Sydney, with the bulk of its physical rides including a ghost train, dodgem cars and the famous ‘Ghost Hunter’ rollercoaster.

Sydney carpenter, Bob, who worked on the interior designs of the rollercoaster, remarked on the lack of direction he and his team were given during construction.

“Theming was not a very common practice at that point. We were given an artists’ impression of what [the design] should look like, but it wasn’t very detailed. We were basically given free reign, so you had to use your artistic sense to do the job,” he recalled to the YouTube channel, Sir Laptop Films.

“When the ride was finished, the Japanese guys wanted someone to test it out, so my partner Vince and I sat on the rollercoaster all day riding it around. It wasn’t until the end of the day that they discovered a couple of bolts were missing from the bottom of the rollercoaster!”

With the park intended as an anchor for the Asia-Pacific region, of which Sega could then establish similar sites across Australia and South-East Asia, it was anticipated Sega World Sydney would attract between 1.2 and 1.5 million visitors in its first year.

Believing the venue would blossom into a multi-level mecca for digital entertainment, prior to its opening, Bermeister announced “Sega World will make existing theme parks look old fashioned”.

Australia’s interactive Disneyland

Sega World Sydney opened in March 1997, attracting about 70,000 visitors in its opening month. A media frenzy surrounded the park’s arrival, who dubbed it ‘Australia’s interactive Disneyland’.

An advertisement campaign was produced to promote the park, which featured Indigenous Australian actor Ernie Dingo exploring the park and hanging out with Sega mascot, Sonic the Hedgehog.

Ernie Dingo with Sega mascot, Sonic the Hedgehog in an ad for the park. Picture: YouTube

The park was divided up into three sections; past, present and future, with rides and attractions fitting the themes of each.

Alongside the nine amusement rides and virtual reality simulators, the park also boasted 200 traditional arcade machines, a food court and live entertainment.

Former Sega World Sydney staffer, Andrew, called the park “really impressive”.

“It was really spectacular. Sydney hadn’t ever seen anything like this before with the really high tech interactive rides. It was very high tech for 1997… I remember feeling very impressed and very proud to have been able to work there when I was only 17 years-old,” he told YouTube channel, Dr Scottnik.

AV manager Noel Burgess told realcommercial.com.au Sega World was more than just an amusement park, but a multi-function venue.

“We had corporate events in there all the time because it was one of the few places where you could host a 1,000-person dinner in the food court and bring in all these caterers,” Mr Burgess said.

“It was the hip new venue in town. And at the time, Darling Harbour was one of Sydney’s newly revamped entertainment precincts. You had Sega World, IMAX and Home Nightclub all opening within a three-year period.”

A big crush

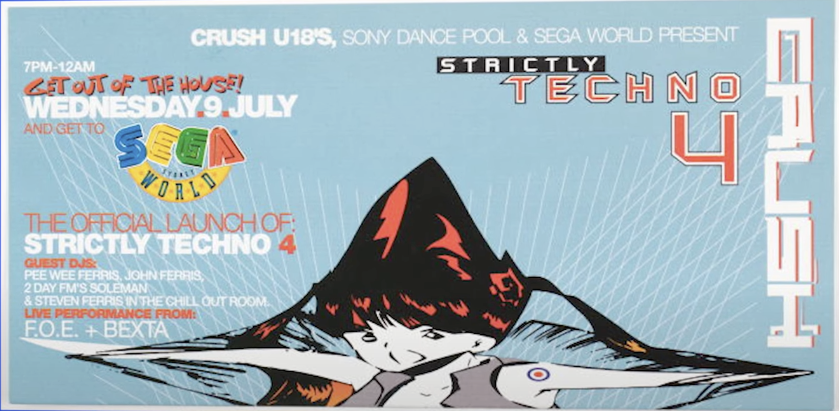

An under 18’s dance party, Crush, surprisingly became one of Sega World’s most popular events.

“You’d have these underage raves happening there every month from 8pm to midnight. Basically 5,000 kids going nuts to trance, house, hip-hop and R&B,” remembers Noel Burgess.

Crush event flyer. Picture: YouTube/DrScottnik

“That was the generation at the time – all into dance music. Many of the ride attendants were ravers who would get into work at 8am on a Sunday after having been out all night.”

Fellow former staffer Peter recalled Irish pop group B*Witched performing at one of the monthly Crush events.

“I remember having to police these teenagers who were trying to find any dark spot to make out in and having to shoo them away!” he told Dr Scottnik.

The downfall

Despite opening seven days a week from 10am to 10pm, only eight months after its launch, Sega World was already struggling to attract enough visitors to make the business profitable.

In November 1997, Sue Williams of the Sydney Morning Herald reported, “it is not the virtual reality attractions that catch your eye; it is the virtual emptiness of the place”.

Sega attempted to cut its losses and sold its stake in the amusement park in 1999. But given it was an investor, Sega had to pay its way out, resulting in Jacfun receiving around $36 million.

It was hoped the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney would boost attendance numbers, however Sega World only managed to attract 400,000 visitors for the year – less than half of its estimated yearly projections.

Darling Walk in the late ’90s. Picture: Sega World Sydney Memoriam/Pinterest

The park also struggled to attract guests outside of holiday periods, despite offering discounted entry and prices. Opening hours were eventually shortened in an attempt to reduce costs.

“I remember around July of 2000, one of the marketing people said they had been asked to cancel Sega World’s Yellow Pages listing. That was the first time where we thought, okay, this probably won’t be here next year,” Noel Burgess said.

In the face of continued losses, Sega World Sydney ceased operation in November of 2000.

The following year, Jacfun and Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority hurriedly auctioned off the remaining attractions and rides from the park at heavily reduced prices, with one ride initially priced at $200,000 selling for $140,000.

The Sega World Sydney building lay dormant until 2003 when, frustrated by Jacfun’s lack of action, the SHFA paid the company $10 million to terminate their 99-year lease of the site.

The Commonwealth Bank of Australia entered into a long-term lease for the property in 2008. Later that year, the iconic Sega World Sydney building and its blue dome roof was torn down.

Ahead of its time?

Despite being widely deemed a business failure, Noel Burgess considers Sega World a unique experiment and moment in time where new technology and culture collided with corporate money.

“Unfortunately, I don’t think people were ready for that kind of thing. Australians weren’t exactly early adopters of technology at the time, especially compared to say the Japanese. And back then, there were no smart phones and the internet had barely begun – we just weren’t used to experiencing media through digital means yet. It was a completely different cultural literacy,” he explained.

“It’s kind of sad really, because now video games are a huge thing. I think if Sega World Sydney were around today it would go gangbusters.”