How a small town’s stand against McDonald’s inspired a national fightback

Almost two decades ago, the sleepy NSW town of Picton found itself at the heart of a burgeoning national debate.

Its residents, led by a defiant mayor, stood firm against the arrival of a fast-food giant, determined to protect their unique ‘heart and character’.

It was a well-documented fight that captured headlines and, arguably, set a precedent for communities across Australia.

But looking back from 2026, with fast-food outlets now a common sight even in Picton, was that initial stand truly worth the effort?

In 2009, former Wollondilly Mayor Michael Banasik became an unlikely hero, leading a vocal charge against the proposed arrival of the town’s first McDonald’s.

Slated for a character residential area, the fast-food giant, he argued, threatened to unleash traffic chaos and erode the very appeal that made Picton special.

RELATED

McDonald’s scraps plans for controversial Sydney restaurant

The rise and fall of a Tex-Mex icon in Australia

Remembering Sizzler: The rise and fall of a dining icon

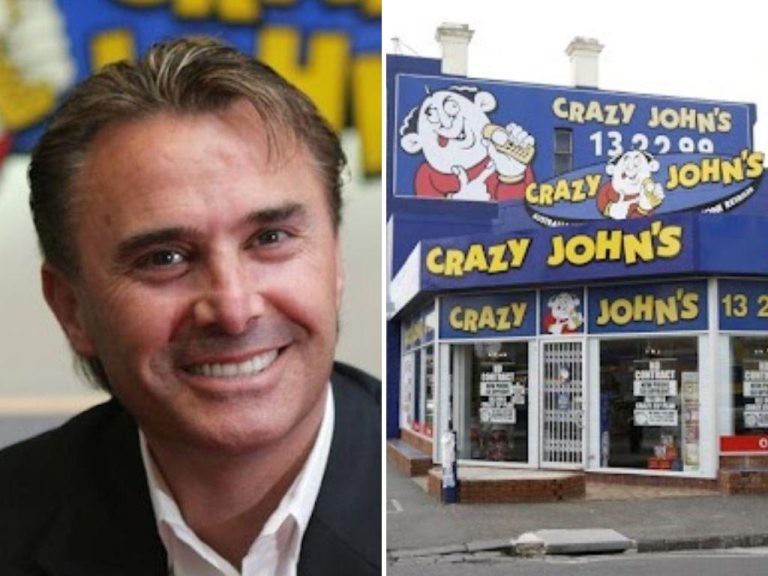

Former Wollondilly Mayor Michael Banasik poses for a photo outside McDonald’s Picton in 2020. Picture: Monique Harmer)

Locals rallied, their collective outcry becoming a significant and well-documented example of public rejection against a fast-food outlet in Greater Sydney, if not wider Australia.

They feared their town, known for its charm, would lose its essence to corporate uniformity.

Fast forward to 2026, and the landscape has shifted dramatically.

MORE NEWS: What ever happened to Hog’s Breath Cafe?

Former Wollondilly councillor and now-local MP Judy Hannan was among a large number of locals who fought the development on the site of a former patrol station.

What was once a significant local stand in Picton is now a national phenomenon. Communities across the country are mobilising, their voices amplified by social media, council submissions, and even acts of defiant vandalism, all to protect their neighbourhoods from the relentless march of corporate convenience.

IBIS World data reveals the number of outlets surpassed 26,000 in 2025, with McDonald’s, KFC, and Hungry Jack’s still dominating the market, according to Roy Morgan Research.

Yet, despite their ubiquity, a growing number of suburbs are fiercely resisting.

Picton revisited: A legacy of learning

So, back to Picton. Wollondilly Council ultimately lost the fight against Maccas, with the Picton outlet opening around 2011 despite the public outcry from residents and councillors alike.

Given the Picton battle was a years-long fight that ended with McDonald’s setting up shop anyway, was that initial, well-documented opposition against the Golden Arches truly worth it?

Current Councillor Benn Banasik, son of the former mayor, offers a reflective perspective. While the community has “well and truly moved on” and the area now boasts multiple fast-food outlets, he acknowledges the profound legacy of that early battle.

“Myself and (former mayor Michael Banasik) tried to fight that stupid thing from getting approved (back in 2009),” Cr Banasik recalled.

Wollondilly Councillor Benn Banasik also wasn’t a massive supporter of Picton’s first McDonald’s but acknowledges that council needs to work with developers and fast food giants. Picture: Wollondilly Shire Council

“He didn’t want it for the appeal for the area…I’m more agnostic to it in regards to that but I thought it was wrong that it didn’t even match the same street appeal as the shops next door. It looked silly.”

Cr Banasik argues that the Picton experience served as a crucial lesson for the council. “Council kind of took the learning from Picton at the time and since then, has approved developments in certain areas like Tahmoor – and Tahmoor is now seen more as a commercial hub and has more of those traditional type of fast food type ventures.”

This strategic planning, he notes, has allowed Tahmoor’s main street to maintain its existing businesses, proving that thoughtful development can avoid job losses.

Store Manager Erica Berdar at the new Picton McDonald’s.

He believes developers often do themselves a “disservice” by not considering alternative, more appropriate locations.

The key, he suggests, is for councils to be “upfront as to where you want things” and to engage openly with applicants, guiding them towards suitable sites.

“I do think that (McDonald’s Picton) was the straw that broke the camel’s back for allowing those types of things to come into the area,” Cr Banasik concluded.

The battle, though seemingly lost in the short term, ultimately empowered communities and councils to think more strategically about preserving the unique ‘heart and character’ of their suburbs.

Redfern’s resounding ‘No’

Back in Sydney, the inner-city suburb of Redfern recently delivered its own powerful blow to the fast-food juggernaut.

A $3 million proposal for a 24-hour, two-storey McDonald’s was emphatically rejected by the City of Sydney Council.

Out of 286 public submissions, a staggering 269 were against the development, which would have introduced one of the ‘big three’ to the area.

The site which was proposed for a 24-hour fast food outlet.

An artist impression of the two-storey McDonald’s in Redfern.

While proponents argued for increased foot traffic and a boost to local businesses, these claims were dwarfed by profound community concerns.

Dhungatti Archibald Prize-winning artist Blak Douglas, a long-time Redfern resident, argued that fast-food giants would undermine First Nations businesses striving to improve local nutrition.

“That’s like one step forward in our community with a focus on native nutrition, and then it’s four steps backwards with a fast-food franchise coming in there,” he told the ABC.

A McDonald’s spokesperson maintained that every restaurant contributes to the local community through job creation and training, and that the company “values community feedback.”

Newtown’s enduring spirit: A tale of two takeaways

Newtown, Sydney’s bohemian heartland, has its own storied history of resistance.

McDonald’s first opened there in 1989, only to close 11 years later, citing “changing demographics.”

When the company attempted a return in 2025 with a 24-hour outlet, the community mobilised with ferocity.

Of 1433 public submissions, a mere six supported the proposal, according to The ABC.

The City of Sydney Council ultimately rejected it, citing a lack of merit, non-compliance with late trading rules, and safety concerns.

Liam Coffey, an 18-year Newtown resident, became a viral sensation with his social media videos documenting the community’s response.

“I think without a doubt, my use of social media has directly impacted this decision,” he declared.

McDonald’s on King Street at Newtown in the early 1990s. (Supplied: City of Sydney Archives)

Yet, the story isn’t black and white.

Last July, KFC made a comeback on King Street, replacing an Indian and Sri Lankan restaurant.

This proposal received only 11 submissions, with one in support, and was approved.

A City of Sydney spokesperson explained the difference: KFC’s plan allocated only 60 per cent of its floor space to kitchen and back-of-house, compared to McDonald’s’ 84 to 90 per cent.

For local businesses like Broaster Chicken Newtown, owned by Md Rubel, the impact has been devastating.

“The last six, seven months it’s going really bad because I think it’s pretty similar food, and obviously we can’t beat the price,” he told the ABC.

A new building in Marrickville had been graffitied with anti-McDonalds messages. Picture: Thomas Lisson

Struggling to pay rent and suppliers, Mr Rubel has taken a second job. He fears a McDonald’s in the area would spell the end for his business.

Even in Marrickville, where a McDonald’s was approved last year via a Complying Development Certificate – bypassing public and council input – community sentiment was clear.

During construction in September, the site was vandalised with “McF*** off.”

The ongoing tension between the relentless expansion of fast-food giants and the fierce determination of Australian communities to protect their local identity is a defining feature of modern urban development.

As more suburbs stand up, the lessons from Picton’s well-documented fight continue to resonate, shaping a future where local charm might just triumph over corporate uniformity.