Banks, balance sheets and bailouts: the March of fear

A branch in Santa Monica of the failed Silicon Valley Bank. Picture: AFP

For listed real estate, the fear across markets during March was palpable. One could almost cut it like a knife.

The initial failure of Silicon Valley Bank, followed by Signature, and then Credit Suisse, has many investors worried about a second global financial crisis. A generation of would-be Michael Burrys, educated and influenced on a steady diet of watching The Big Short, have been looking for a potential culprit – naturally their gaze falls on real estate.

The concern is the almost $3 trillion of commercial real estate loans sitting on US bank balance sheets – a disproportionate amount of which is with smaller, less well-capitalised banks.

The concern is that since office buildings are being abandoned by their tenants, it follows that they will soon be abandoned by their owners, landing on bank balance sheets precipitating a credit crisis, a collapse in several banks, real estate values, and ultimately, another credit crunch.

Read more:

Business loans

Small business loans

Business lending and equipment financing

What you need to know about commercial loans

Scary stuff. But are there troubles ahead in commercial real estate? Probably.

Total commercial real estate loans with US banks amount to almost $3 trillion, while loans with smaller and regional banks are at about $2 trillion. This is where there is some concern.

These banks are significantly smaller than the majors, yet carry a disproportionate share of the real estate loans. These loans include multifamily and rural loans which are unlikely to suffer any significant stress, especially since multifamily rents have increased by near double digits per annum for the past two to three years. We suspect there is plenty of equity in these loans.

Therefore, non-residential commercial real estate loans work out to be a little over $1 trillion. This includes office, retail, self-storage, industrial, service stations, restaurants, hotels, data centres, and the remaining spectrum of commercial real estate.

However, office and retail make up a large proportion of these loans – according to JP Morgan research, roughly 40 per cent and 25 per cent respectively. While there may be some issues with retail, most of the focus is on the office space – or $400bn of office loans.

So, how bad can it get?

If we assume a delinquency rate on all office loans of around 15 per cent (an all-time 30 year high), which seems conservative enough, the next assumption is recovery rate. Of the loans that fall past due, not all suffer a loss. Banks could recover the amortised loan amount or the loan could be sold to financial specialists that work out high leverage assets at or close to par.

Assuming this 15 per cent delinquency rate with a corresponding 80 per cent decline in office value, banks would face a $39bn loss – which in turn represents just over one twentieth of their book equity. Hardly a disaster.

Michael Burry, the former hedge fund manager who predicted the US housing market’s plunge. Picture: Bloomberg

This analysis is based on aggregate data from the US Federal Reserve and, as such, makes no assumption or comment about individual bank exposure. Clearly, banks with higher exposure have higher risk, and eventually may generate more headlines.

Secondly, delinquency rate and asset values are not independent variables. As one rises, the other factor rises with it. If all office values fall more deeply, it can be argued the delinquency rate may well be higher.

On the positive side, the losses assumed are cumulative, and are likely to occur over several years. Meanwhile, banks will continue to earn yearly net interest margin and return on equity from other loans, courtesy of existing lease duration to buffer or offset the losses.

This is an important distinction from the housing crisis in 2008-09, where non-income producing mortgages with no lease duration defaulted very quickly. And where loan values were sometimes higher than the initial loan due to so-called “teaser rates”.

And while office is indeed challenged in the current environment, we do not believe work from home culture will spell the end of the asset class.

Anecdotally, industry contacts inform us today that some of the major cities in the world have recovered to near 90 per cent peak day occupancy in cities such as London, New York and Boston, while leasing volumes – while down on pre-Covid levels – are not disastrous.

Office leasing volumes across major markets are back to pre-Covid levels, albeit with softer rents. Stress in private label CMBS remains very low – probably reflecting initial conservative underwriting, since as an asset class, office was a poor performer in the decade prior to the pandemic. Again, another distinction from the 2008-09 housing crisis.

As we have seen from other bank failures, if depositors flee, then despite high quality loan books a bank will run short of reserves and be unable to settle transactions on behalf of customers. This is not disastrous so long as the interbank market continues to function, and the loss of deposits are lent back.

This is beginning to happen to the smaller banks. For now, the loss of deposits is currently covered by increased loans – almost certainly from the Central Bank and other US banks – showing the interbank market, for now, is functioning as it should.

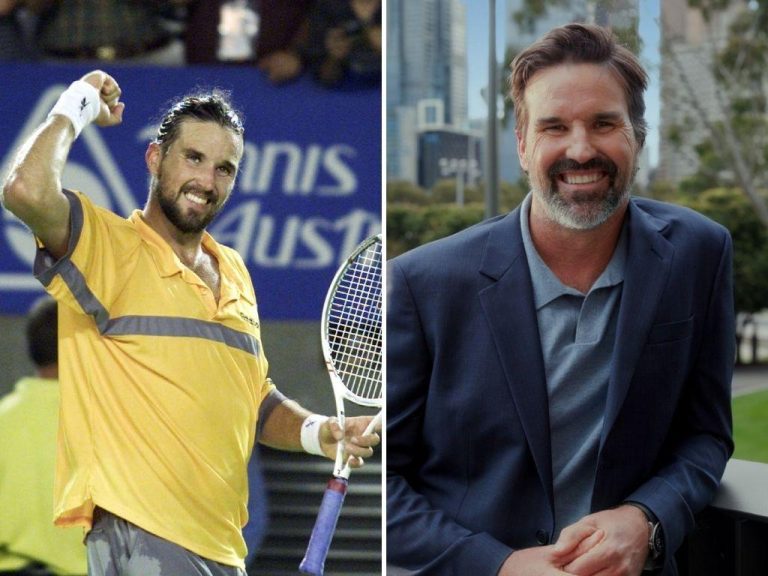

Chris Bedingfield, a principal of Quay Global Investors.

The lesson here is that banks can fail irrespective of asset quality. Until regulators and the government mandate something that resembles near 100 per cent reserve backed deposits (while ensuring discipline on the asset side of the balance sheet), then pretty much all banks, globally, are vulnerable.

While our broad analysis suggests small commercial banks may be able to manage the losses, there is a fear that appetite to maintain or extend more credit will be compromised – at least in the short-term. This is a fair expectation.

However, it’s important to get the technicals of modern banking right. It’s tempting to observe the recent drop in deposits of the smaller banks and conclude they will not have the funding to maintain lending.

This is not true – deposits are not required to make a loan. The loan creates the deposit. Banks create their own deposit base via the lending process.

The limit to extending credit is risk appetite and equity risk capital.

In a tighter lending world, assets that are highly leveraged may be required to find additional funding via equity or mezzanine debt, where old equity holders will be diluted.

However, we believe there will still be appetite for lending from larger banks as well as the smaller banks. Outside of office, the underlying performance of real estate globally is generally good and cashflows are robust.

And as our earlier example shows, refinancing debt from 3 per cent to 7 per cent after five years is easily covered by moderate growth in rental cashflows.

This is in stark contrast to the housing crisis in 2008 where housing and defaulted mortgages had almost no income, and a shortage of creditworthy borrowers in an 11 per cent unemployment economy.

Most REITs, although not all, have learned the lesson of 2008 and have access to liquidity via cash on hand and undrawn lines of credit. They can therefore continue to operate with access to capital in the near to medium term.

Chris Bedingfield is a principal of Quay Global Investors