Bank, market economist diverge on housing price forecasts

The HIA estimates two million homes are needed over the coming decade to meet the demand for housing.

Doom and gloom predictions about the residential property market’s future have been creeping into the mainstream since the cycle hit its peak exactly a year ago.

But after a period of extraordinary price increases, Australia’s property forecasters appear to be hit a crossroads about what happens next.

Homeowners around the country who bought ahead of 2020 saw their homes gain a quarter of their value in just 12 months across most of the country, in what turned out to be one of the sharpest and most widespread booms on record.

The future trajectory, however, is more uncertain. Sydney and Melbourne’s values have mellowed, while the smaller markets continue to tick along at increasingly slower rates of capital gains.

PropTrack data for March showed a further slowdown in the cost of housing, up just 0.68 per cent last month across all dwelling types. Three capital cities showed minute falls (Melbourne, Perth and Darwin) while Sydney, Brisbane and Adelaide slowed. According to monthly price indexes and auction clearance rates. CoreLogic auction clearance numbers also showed a decline in the number of homes selling, although last weekend seven in 10 still sold under the hammer nationally.

Bank economists expect values to fall in the coming 12-24 months. Westpac and CBA are both tipping a rate rise in the first quarter of the upcoming financial year. The former is the most bearish in its predictions at 14 per cent drop, while CBA – the biggest of the big banks – is anticipating a 10 per cent drop over 2022. ANZ expects a far smaller 4 per cent.

CoreLogic’s Tim Lawless said forecasts were generally founded on three core market impacts – interest rates, costs and the broader economy. Despite the economy being strong – with wages tipped for growth, unemployment at a record low and inflation increasing – interest rates are expected to grow in the near-term and fixed mortgage rates have doubled in some cases from less than 2 per cent.

CoreLogic research director Tim Lawless.

Given that more than a million borrowers have never experienced a rate hike, CBA’s head of Australian economics Gareth Aird last week raised concerns it may have an impact on broader market sentiment.

AMP chief economist Shane Oliver expects prices to even out at a 1 per cent fall by the year’s end before recording a peak to trough decline of 10 per cent to 15 per cent pushing into 2024, led by the Sydney and Melbourne markets. He noted that the current crawl of house prices upward is likely to angle south by July.

“It’s mainly a function of the fact that the monetary cycle is now tightening and historically that’s led to a downturn in the property market,” Dr Oliver said. “The combination of record-low interest rates, particularly fixed mortgage rates, and FOMO (fear of missing out) brought forward the recovery, but it would have normally occurred more slowly and more gradually.

“Likewise … the market has become more sensitive to fixed rates, whereas it used to be variable rates.”

The timing of the market tipping could ring true, with the likely market slowdown from multiple consecutive long-weekend disruptions through April and general political uncertainty in the lead up to the election possibly acting as catalysts for quieter conditions.

Should the market turn as the predictions suggest, it will be one of the most significant corrections on record, Mr Lawless said.

Using Sydney as an example, prices rose 28 per cent within 16 months over the short and sharp pandemic boom. The previous upswing between 2012 and 2017 ran 66 months to achieve an increase of 75 per cent. The immediate correction saw prices retreat just 25 per cent over two years. On that basis, Mr Lawless believes declines will be “not as significant”, describing the predicted double-digit falls as “not unreasonable but could be pessimistic”.

But an increasing number of economists are leaning in to the strengthening economy as a basis for a stronger market outlook.

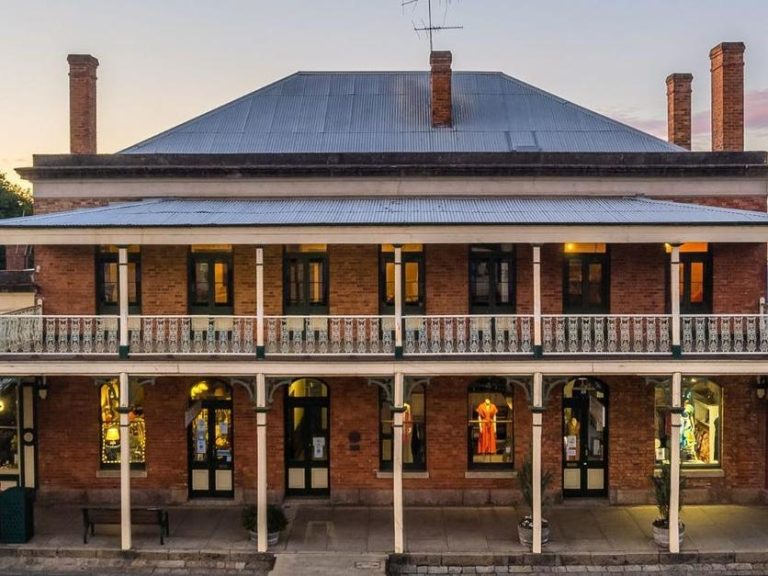

The market slowed further through March, with PropTrack data noting a rise of just 0.68 per cent. Picture: NCA NewsWire / Gaye Gerard

Seller and buyer behaviours have also informed PropTrack’s forecast of 6 to 8 per cent gains in the coming year. Economist Paul Ryan said a plateauing hold pattern is not out of the question come 2023.

“The thing about interest rates is they’re not set in a vacuum is that the RBA is waiting for really, really strong economic conditions before they are increasing interest rates,” Mr Ryan said.

“The RBA does not want to raise interest rates so quickly that it shocks people‘s finances. They just want to take a bit of heat out of the market and take a bit of money out of everyone’s pockets.”

While Housing Industry Association’s chief economist Tim Reardon did not suggest a forecast of his own, he dismissed some of the overly bearish predictions.

“The market is expecting interest rates to rise to 2.5 per cent (from 0.10 per cent) by the end of next year and that’s not going to happen,” Mr Reardon said.

“The prospect that we’re going to see the market overall decline over the next 13 months when we have wage growth, low unemployment and a return migration, it’s challenging to see how that dynamic plays out.”

PropTrack senior economist Paul Ryan.

Mr Ryan also noted buyers were unlikely to be deterred from transacting but cautious about over-committing themselves. However, addressing Mr Aird’s concerns about rate rises, he said many new borrowers will have “fat in their budgets” based on APRA’s serviceability buffer to ensure mortgages are paid without homeowners being forced to sell.

“It‘s more around that the psyche may change and those recent buyers may get a shock that it can be difficult to pay down a mortgage after the first couple of years,” Mr Ryan said.

As far as 2022 predictions go, SQM Research managing director Louis Christopher noted his prediction of 0 to 5 per cent growth nationally through 2022 was on track over the first quarter of the year. When pressed on his predictions beyond that, he said it is a fool’s game.

“It’s extraordinarily brave for anyone out there, whether you’re an institution or public individual, to make a forecast for 2023,” Mr Christopher said.

“You tell me what’s going to happen with inflation, with interest rates, with immigration, with any potential change of government and whatever housing policies they come out with, whatever may well do. These are all factors which can have a significant influence upon the market.”

Last week’s budget largely addressed rising cost of living pressure in the lead up to the likely May election, with the main housing focus on expanding the Home Guarantee Scheme expanded to 50,000 places for the coming three years.

Dr Oliver warned while it was unlikely the additional places within the scheme – which allows particular groups to access the market with a deposit of as low as 5 per cent – are unlikely to drive property prices higher, it could set a new floor in the market.

The only true answer to affordability is adding more properties to the market, said Mr Reardon. It is a notion supported by both the federal government’s inquiry into housing affordability and supply and the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation.