More pain before pleasure in industrial property sector

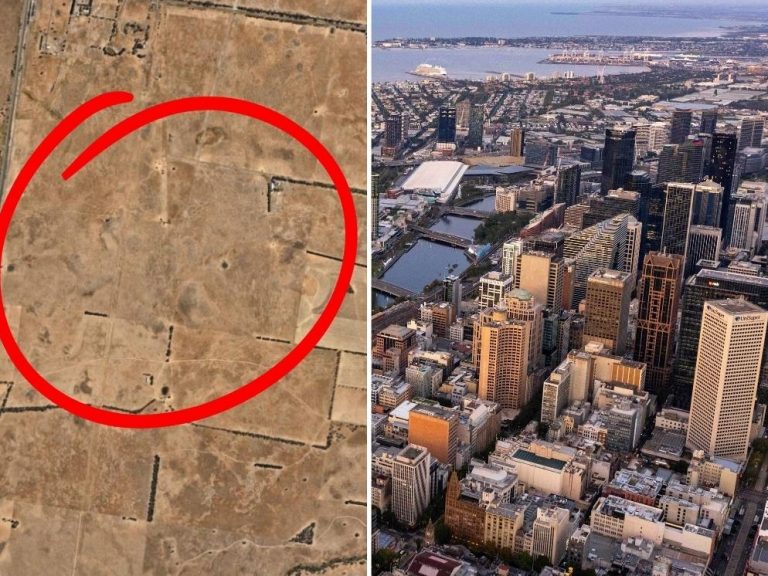

Work continues at Badgerys Creek in western Sydney on the site of the new airport. Picture: Richard Dobson

One of the country’s most experienced industrial property investors, Pipeclay Lawson’s David Libling, has warned that the sector faces a significant resetting of values.

Libling, who has a three-decade history in the field, sold a portfolio of logistics properties to US group Hines in April. They traded for $211.5m on a sharp yield of about 3.48 per cent – which he does not think could be repeated today. The sale delivered a 37 per cent internal rate of return after all fees over seven years to Pipeclay’s investors.

While he admits his timing is not perfect – his firm sold in 2006 ahead of the pre-GFC market peak – Libling argues that the same patterns apply.

Pipeclay’s sales this year meant it had sold down more than 80 per cent of its $400m worth of holdings after also selling in Queensland in 2021. “We thought it was overvalued,” Libling says.

“And we will get back into the market when it’s attractive buying again.”

But for now it is all about bond rates.

Libling argues that the industrial property market is priced off the 10-year bond rate with yields ranging from 50 to 500 basis points above this level, depending on individual property characteristics.

The connection sometimes breaks down, as it did ahead of the GFC when there was effectively no premium for owning property, rather than risk-free bonds.

This time he sold when bonds were about 3 per cent. “There was still a bit of a premium, but a truly inadequate one,” he said. His selling was not at the peak – another property sold in the Sydney suburb of Prestons for $58.3m on a 3.3 per cent yield.

Libling expects bond rates to go even higher, which he says means that yields on properties will rise, with industrial deals now being done at about 4 per cent. “There’s another at least 100 and possibly 200 basis points of change coming in industrial property yields in my book,” he said.

And, he says, recent transactions in Brisbane show the market has clearly moved by 50 basis points, with major agencies telling the group that its portfolio would sell at a yield that was 25-50 basis points higher.

Libling distinguishes between Sydney’s classically land-constrained industrial market and the rest of the country. While it is the epicentre of growth in e-commerce and population, and rents are rising, there is more supply than historically.

The unlocking of Kemps Creek and Badgerys Creek for development has changed the dynamic. Libling estimates there is eight to 12 years of industrial land available for development in those areas and big tenants will start to strike leasing deals next year ahead of roads and other connections opening.

This will put a cap on rents, he argues. “I don’t see the rental growth continuing at this fantastic rate we’ve experienced in the last 12 or 24 months,” he said.

But he expects the industry’s large players to weather the changes. The large funds houses and listed players often get in early and will be able to complete projects on the basis of lower historic land costs.

More recent buyers, who were expecting low yields to continue, could be in a tougher spot as a kind of reverse quantitative easing comes into play. “Now, if banks are going to quantitative tightening … the very reverse process has to take place. And also values must fall,” he says.

Libling remains a believer that the quantum of industrial property will keep on growing and will re-enter the market when yields have fully reset.

“The trend to larger facilities has been pronounced over the last 10 years and will continue. To offer the same spread of geographic and tenant risk and opportunities, Pipeclay will become bigger than the $400m we grew to – we‘ll probably need to be twice that size,” he said.